Challenges and opportunities for secondary education in Latin America and the Caribbean during and after the pandemic

Work area(s)

Topic(s)

Teaser

The pandemic has had a critical impact on the educational trajectories of children and adolescents in Latin America. Video-call interviews with more than 150 students, teachers, and parents in eight countries in the region (namely, Argentina, Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, Chile, Ecuador, Costa Rica, Honduras, Mexico, and Uruguay) in 2020 and 2021 reveal the challenges and opportunities faced in the transition to remote and online education during lockdown.

Laura Rodríguez

Master’s in Latin American Studies, University of Amsterdam,

Centre for Latin American Research and Documentation (CEDLA)

The pandemic has had a critical impact on the educational trajectories of children and adolescents in Latin America. Video-call interviews with more than 150 students, teachers, and parents in eight countries in the region (namely, Argentina, Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, Chile, Ecuador, Costa Rica, Honduras, Mexico, and Uruguay) in 2020 and 2021 reveal the challenges and opportunities faced in the transition to remote and online education during lockdown.[1] This situation has brought many challenges for students in the framework of the pandemic and exacerbated the existing digital and learning gaps. However, new opportunities have also emerged, which must be taken into account in the design of education policies in the post-pandemic world. While it is true that students would have acquired the knowledge included in the curriculum much more easily in in-person classes, it is wrong to assume that they did not learn anything of value during the pandemic academic year. This article analyses the main challenges, reversals, and consequences, as well as the opportunities, for secondary education in Latin America and the Caribbean during and after the pandemic.

I. Educational inequalities pre- and post-pandemic

In Latin America, the expansion of secondary education has been accompanied by segmentation and social exclusion processes. Historically, secondary education systems assumed that the elites did not need to acquire abilities related to the production and distribution of goods and services and that manual labourers did not need to acquire knowledge associated with socioeconomic processes and the cultural aspects of society (Braslavsky, 2001). This system of segmentation and social exclusion contributed to maintaining the status quo and limited the opportunities of the more vulnerable sectors of society (López, 2019). Although advances have been made in expanding access to education in recent decades, there has also been a high degree of segmentation in terms of both achievement and the quality of the services provided (Acosta and others, 2021). This has perpetuated inequality across generations, not because some have access and others do not, but because individuals have differentiated access in terms of education quality, as well as opportunities for interaction and the construction of social and cultural networks for the future, which will have a direct impact on their development capacities.

Prior to the pandemic, Latin America was already considered one of the most unequal regions in the world with regard to income and development opportunities. These inequalities were exposed and even exacerbated by the COVID-19 crisis (Elacqua, Marotta and Méndez, 2020). Almost two years into the pandemic, the region is facing an education crisis. To slow the spread of the virus, mass school closures were declared, and remote and online learning was thus adopted as the most commonly used educational strategy in educational establishments. However, due to the digital gap and the inequality in family and school resources, the distance learning formats did not have the same impact throughout the population (Ministry of Education, 2020). Moreover, these strategies are implemented unequally and can widen the educational gap (García Jaramillo, 2020).

Diagram 1

Latin America (18 countries): How prepared were Latin American educational systems for the crisis?

Source: S. Rieble-Aubour, “COVID-19: Are we prepared for online learning?”, Brief, No. 20, Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), April 2021.

Diagram 1 shows the degree to which the educational system was prepared to implement digital education alternatives before the arrival of COVID-19, for eighteen countries in the region. The results of the study show that Uruguay had the best conditions, followed by Chile and Colombia.[2] At the other extreme, Nicaragua, the Plurinational State of Bolivia, and the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela had more precarious conditions. The rest of the countries recorded suboptimal conditions in at least three of the five dimensions considered.

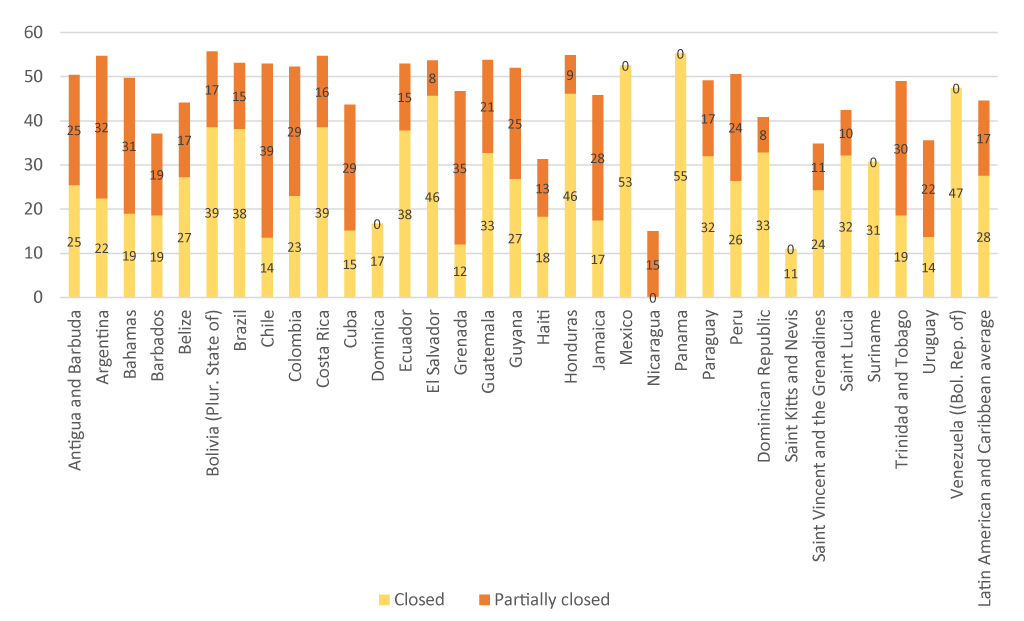

To date, the longest school closures in the world have been in Latin America and the Caribbean (Turkewitz, 2021). The countries in the region have, on average, gone more than an academic year (40 weeks) with no in-person classes or with long periods of interruption (see figure 1). As of 31 May, in the majority of the countries in the region, education centres remained totally (8 countries) or partially (18 countries) closed. Schools were operating at full capacity in only 7 of the 33 countries in the region (ECLAC, 2021). The disruption of in-person learning has affected 167 million students at all educational levels (ECLAC/UNESCO, 2020).

Figure 1

Latin America and the Caribbean (33 countries): Length of the full or partial closure of the in-person education system (primary, secondary and tertiary education), 16 February 2020 to 31 May 2021

Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), “The recovery paradox in Latin America and the Caribbean Growth amid persisting structural problems: Inequality, poverty and low investment and productivity”, COVID-19 Special Report , No. 11, Santiago, July 2021, on the basis of data from United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), “Total duration of school closures”, 2021 [online] https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse#durationschoolclosures.

While education processes have continued remotely, using digital or traditional means (such as TV or radio), the effects of the digital gap have been amplified in the case of rural and lower-income populations, which have lower access to connectivity and lower skills to take advantage of this type of technology. This is extremely important since at least 66.2 million households in the region do not have an Internet connection (data on 14 countries) (ECLAC, 2021). Despite efforts by the authorities, the prolonged health crisis will have long-term consequences on these generations of students. There will be delays and an increase in learning achievement gaps that will be hard to recover in the short term. The loss of learning due to lack of attendance is estimated at up to a year of schooling (García Jaramillo, 2020).

School dropout is another important consequence of the pandemic. An estimated 3.1 million children and adolescents in Latin America and the Caribbean may never return to school as a result of the pandemic (Seusan and Maradiegue, 2020). Furthermore, the probability of completing secondary school in 18 Latin American countries is estimated to have fallen from 56% to 42%; the effect is strongest among adolescents in families with a low level of education, whose probability has dropped almost 20 percentage points (Neidhöfer, Lustig and Tommasi, 2021). Experts fear that if emergency recovery and re-enrolment measures are not implemented, the region could be facing a lost generation, similar to countries that have suffered years of war (Turkewitz, 2021; ECLAC, 2021; ECLAC/PAHO, 2021).

Secondary education is crucial for citizens’ educational and professional attainment since this stage often determines whether young people will continue on to higher education (López and Tedesco, 2002). Finishing secondary school is important not only because it allows young people to acquire the necessary knowledge and skills to live in a globalized world, to participate freely, and to be able to learn throughout life, but also because it prepares them to be successful in the labour market and thus breaks down the mechanisms that reproduce inequality (Trucco, 2014).

II. The challenges and opportunities of remote and online learning during the pandemic

A. Challenges

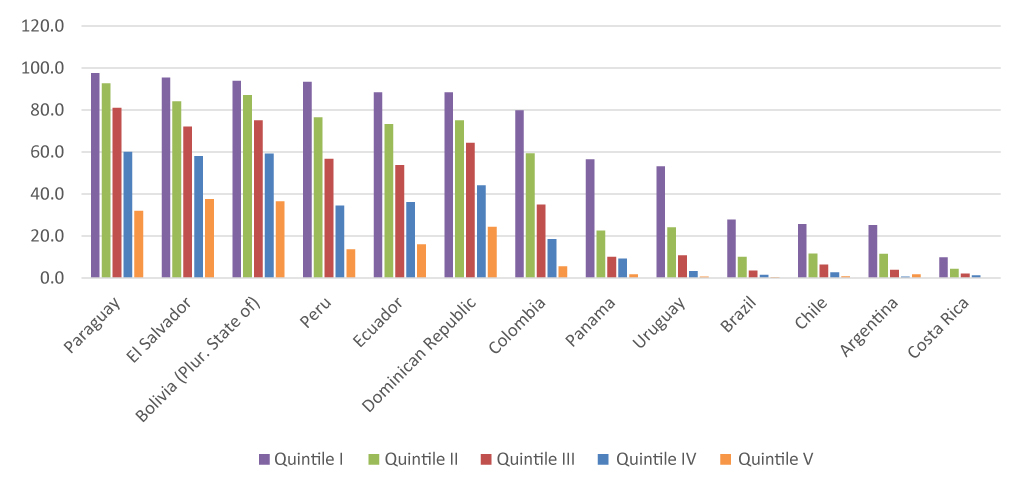

During the pandemic, three major challenges have arisen in the transition to distance education through digital means. The first has to do with the lack of access to the Internet and technological devices. Today, less than 50% of the region’s population has a broadband Internet connection, and only 9.9% has a high-quality fibre-optic connection at home (Drees-Gross and Zhang, 2021). Online learning is only possible for those who have an Internet connection and access to devices. Unfortunately, 36% of children between 5 and 12 years of age in the region live in households that are not connected to the Internet. In the countries for which data are available, this implies excluding over 17 million children (see figure 2). Furthermore, even in countries with higher connection rates, around 30% of these children do not have an Internet connection at home (ECLAC, 2020).

Figure 2

Latin America (13 countries): Households with children that have no Internet access, by quintile

(Percentages)

Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), Regional Broadband Observatory (ORBA), on the basis of Household Surveys Databank (BADEHOG).

Household access to digital devices is also unequal in the region, especially among students pertaining to different socioeconomic and cultural contexts. While 70% to 80% of students in the highest socioeconomic settings (fourth quartile) have laptop computers at home, only 10% to 20% of students in the lowest quintiles (first quartile) have these devices (see figure 3) (ECLAC, 2020). Isaías, a teacher in an institute for low-income families in Chile, said that “although the school got old tablets and laptops for the students, only around 2% could connect to the Internet and participate in the online classes, because the majority lack the resources to access the network”.

Figure 3

Latin America (7 countries): 15-year-old students who have digital devices at home, by type of device and socioeconomic quartile, 2018

Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC)/United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), “Education in the time of COVID-19”, COVID-19 Report, Santiago, August 2020, on the basis of data from Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), 2018.

In vulnerable contexts, the economic difficulties and weak cultural capital often imply an absence of family support for the students’ education, which also plays an important role. Rebecca, a computer science teacher at a middle-class school in the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, said that “for vulnerable families, it is more important to buy food than notebooks". These students frequently lack sufficient support from their parents during the learning process and, in the worst cases, leave school to work and contribute financially to the household.

The second challenge in the transition to online distance learning has to do with the lack of socioemotional skills (such as discipline, motivation, and time management) and the digital skills necessary to adapt to this teaching modality. While it is essential to implement measures to guarantee that students have access to the Internet and devices, this is only the first step in facilitating students’ success in online distance education. The difficulties tied to remote learning, especially in the context of the health crisis, go beyond unequal access to resources. Students’ general lack of digital skills has been brought to light. Many teachers expressed disappointment that adolescents demonstrated the ability to use the Internet and devices for entertainment, but not for educational purposes. A survey of teachers in Chile finds that only a fourth believe that their students have the necessary skills to use remote work applications, and only 9% consider that the majority of their students have independent study habits (SUMMA, 2020).

A study conducted by the World Bank to estimate the effectiveness of measures to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 shows that in Chile, where many educational establishments offer online classes, distance learning would only be able to mitigate between 30% and 12% of the loss of learning associated with school closures (Ministry of Education, 2020). Even when there are support strategies and coverage, it is difficult to maintain the students’ participation, motivation, and commitment (Ministry of Education, 2020). Additionally, the anxiety and stress caused by the uncertainty and lack of social contact during the pandemic affected adolescents’ mental health, motivation levels, and academic performance (UNICEF, 2020). This again highlights the importance of acquiring the socioemotional and digital skills to be able to participate successfully in distance learning formats.

The third challenge in the transition to online distance learning during the pandemic was the inadequate adaptation of teaching methods to the virtual environment. The use of study guides was the most accessible teaching method for the majority of educational establishments because they could be easily shared via WhatsApp messages. Although some teachers adapted their teaching methods to the digital format, assigning projects that would require filming, editing, and even content creation through social networks, these cases do not represent the experience of the majority of students. According to a survey carried out in Chile, 56% of teachers sent their students study guides or resources (physical or virtual), but they did not hold classes. Only 18% reported having synchronous classes, which were concentrated in private schools and secondary education (Educar Chile, 2020). A third survey of teachers in Chile shows that teaching activities during the pandemic have mainly been based on sending out activities (81%) and homework (75%) for the students to work on independently (IIE, 2020).

Students who said they were graded based on the use of study guides expressed feeling like they met the requirements without really understanding the content. Oscar, a student at a private school in Costa Rica, mentioned that “I haven’t learned anything in physics or chemistry since the start of the pandemic”. Hugo, a student at a private institute in Uruguay, said he felt like he had passed his classes by “just copying and pasting the homework”. Consequently, most of the students interviewed signalled that they had learned very little from the remote or online classes.

B. Opportunities

Distance learning formats also generated new opportunities for students. First, these learning formats gave students the incentive to develop socioemotional or transversal skills to meet their academic goals during lockdown, such as the ability for self-motivation, discipline, responsibility and time management. Interviews with students in Honduras[1] show that to relieve stress and depression during lockdown, some adolescents watched motivational videos on YouTube, took walks or exercised, among other activities. Others mentioned finding an outlet or relief in subjects such as art, English, and psychology. Many of the students who were able to stay motivated under these circumstances did so in the hope of being admitted to the university programme of their choice or of finding a good job so they could “be someone in life”. Thus, the pandemic demonstrated the importance of socioemotional skills in learning processes, in general, while providing the incentive for students to develop these skills.

Second, students developed a wide range of mostly creative abilities. The independence created by the greater control over their time led many students to take up new hobbies and acquire new knowledge and skills, most not directly related to their classwork, such as learning a new language, cooking, or playing a musical instrument. In some cases, these experiences prompted the students to consider going into professions they had not previously considered. José, a student at an institute in the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, learned to bake different kinds of bread and to play music. He says he started learning with the help of his family and later used videos on the Internet. Based on this experience, he started thinking about a possible career as a baking and pastry chef: “I love everything about making pastry. I’ve watched a lot of cooking videos on YouTube. … I’ve also learned to play the guitar. My uncle plays several instruments, so I decided to learn, too.”

Katherine, a student at a private school in the same country, enrolled in online language classes during lockdown to learn to speak Korean. She now plans to apply to universities overseas after she finishes her baccalaureate programme. Her classmate, Julián, learned to play the guitar by watching videos online, and he joined Rotary International during lockdown. Although these experiences were all virtual, they inspire students to imagine a future beyond their hometown. Julián mentioned that another classmate began to take music and dance classes during lockdown. When asked if he thought his friend would have participated in these activities if there had not been a pandemic, he said that he did not: “No, now that we’re studying from home, we can do activities in the morning that we wouldn’t normally do.” In this sense, the students’ independence in terms of time management allowed them to explore paths and careers they had not considered before. This type of opportunity mainly arose for students in families with a more advantageous economic position, where living conditions provide a baseline of possibilities.

As might be expected, only students whose schools implemented teaching tactics adapted to the digital environment, such as the use of interactive digital games and platforms in class, managed to improve their digital academic skills during lockdown. Although most of these schools correspond to privileged socioeconomic strata in which it is common for students to have access to the Internet and devices, there are exceptions. Diana, who teaches literature in a low-income institute in the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, assigned video creation projects instead of just written homework, because she thinks this kind of task helps students develop the skills they will need in an increasingly digital world. Thus, the pandemic created space for teachers to use greater flexibility and innovation, allowing them to adapt their practices to their students’ needs.

III. The role of teachers in the transition to online distance learning

Interviews reveal that it was the teachers who led the way in terms of the development of digital skills in the classroom. When asked if the students had suggested applications or software to use in online classes, the majority of the teachers admitted that this was not the case. Although adolescents are generally considered to be more knowledgeable about technology than adults, the interviews indicated that students are not very informed about —or interested in— using digital tools for academic purposes. As described by Rebecca, a teacher in the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, “I have almost a hundred students, and only one suggested a digital platform to use for class activities.”

During the pandemic, teachers often had to learn to use digital tools with little support from the schools, and in many cases, they covered the cost of their own devices and Internet plans. Additionally, they showed initiative in finding ways to accommodate students who did not have access to devices, such as personally delivering study guides. Manuel, a business administration teacher in Chile, used tools like Kahoot, Nearpod, and Menti to make his classes more interactive and fun, while Nina, who teaches history at a private school in the same country, let her students record TikTok and YouTube videos as part of their graded homework. Nina added that, surprisingly, students who did not usually stand out in class often shined with these new types of assignments. This shows that making space for creativity can motivate learning in students who do not feel stimulated by more traditional educational methods. Learning is a complex process that involves cognitive and socioemotional skills that require motivation, participation and interest. Thus, the pandemic highlights the importance of giving teachers room for flexibility and innovation and represents an opportunity to incorporate a more comprehensive approach to learning at school.

Another key aspect of teachers’ experience during the pandemic was the increase in the workload. Not only did teachers have to learn to use different technologies, but they also felt the need to provide emotional support for their students beyond what was stipulated in their work plans. Several teachers commented that they would frequently receive messages from students expressing concern for the school closures. Cristina, a religion teacher at a low-income school in Chile, asked the school for support to enrol in a grief workshop: “I’m in charge of emotional support and containment at the school. … I got the school to pay for me to attend an emotional containment workshop, but it was very basic, so I had to improve my knowledge on grief on my own. This year, I’m working in emotional containment every day. I have to create a teaching plan for the whole month, from first through eighth grade.” As might be expected, this additional workload for teachers, as well as the lack of social contact, has often had an effect on their mental health. In that regard, Cristina noted the strain: “Over the past year, some teachers fell apart because they didn’t know how to work with the Internet or a laptop. … Many teachers are on medical leave because they just can't take anymore. Their energy is exhausted.”

IV. The role of families in the transition to online distance learning

Studies show that it is crucial for students to trust in their own abilities if they are to be successful academically (Urdan and Pajares, 2006). In this sense, their parents’ or caregivers’ confidence in their educational abilities is also important. José and Rafael, brothers and students in a subsidized school in the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, faced the lockdown fairly well. Despite having different personalities, they both were optimistic about the post-pandemic world and acquired knowledge and skills related to their interests in this period. Both were also proactive in addressing the academic limitations of distance learning. As their mother noted, “[My sons] have developed new skills and sought out new information because I always tell them that they should learn more about what they like. Rafael, for instance, took drawing classes, and José studied music.” She often reminded them that they should continue studying and preparing for the future. This suggests that having parents that encourage their children’s capacity to act has a positive impact on students’ development and learning, even in the face of adversity.

The importance of the family for students’ educational attainment is also demonstrated in the case of Abigail, a student in Uruguay who said that her mother is the reason she has been able to continue carrying out her duties during lockdown. Another example is Daniel, who learned to manage his study time by spending more time with his stepsisters. He noticed that they have a set schedule from the time they get up, including when they eat and study, and he decided to follow their routine. He thus learned to manage his time more efficiently and even began to track his academic progress using Excel spreadsheets.

Unfortunately, students in vulnerable situations have fewer opportunities to form these habits, given the social and economic pressures and difficulties faced by their families and their lower accumulation of cultural capital. Manuel, a teacher in a low-income school in Chile, described the situation as follows: "In this context, sometimes there are no parents, just grandparents or caregivers. The parents work all day. … There are families that simply do not have the mental space to worry about school.” Another teacher, Diana, similarly identified a lack of study habits in her students, which in some cases could be attributed to the family environment: “[The students] have little reading comprehension. Around 98% of the kids say they don’t have books at home, don’t have good Internet coverage and some don’t even have computers or smartphones.”

V. The gender gap in the transition to online distance learning

The gender gap has also played a role in students’ pandemic experience. The situation of young and adolescent girls in the region was already challenging before the health crisis. Although statistics show that there are practically no gender gaps in terms of access, there are still gaps in school dropout (UNESCO/UN-Women/Plan International, 2020). Prior to the pandemic, girls carried out more household chores and care work at home than boys. In Ecuador, adolescent girls spend more than twice as much time doing unpaid domestic work as adolescent boys, and in Mexico and Peru girls aged 12 to 17 years spend a third more time doing chores than boys in the same age range. These gender differences demonstrate that the sexual division of labour between men and women is already established in adolescence, which affects the amount of time available for studying (ECLAC/UNICEF, 2016). As a result, completing their schoolwork during the pandemic was particularly difficult for young and adolescent girls, especially those in vulnerable households. While wealthier families have the resources to hire tutors to help their children with schoolwork, middle- and low-income families often depend on older girls to act as tutors and caregivers for their younger siblings.

One student in Costa Rica mentioned that during the pandemic, she had become her sister’s “nanny and tutor”. While many female students regularly helped their younger siblings before the pandemic, the transition to digital education increased the weight of household responsibilities. Furthermore, since parents consider their older children to be “experts” in technology, they often ask them for help. A student in Honduras described her increased responsibilities as follows: “[My sister] would be assigned homework, and my mom doesn't understand much technology, so I’m the one who has to help her. … I receive the assignments and send them in, and I get up early because my sister has virtual classes. It’s been a bit of an overload. … I’m up until 11:00 at night doing homework for the next day.” Similarly, testimonials gathered by Plan International in the region reveal that in some cases, girls cannot even attend online classes because of the amount of domestic work they have to do (UNESCO/UN-Women/Plan International, 2020). In many cases, parents leave their daughters in charge of the family and household chores, while the other members work in wage jobs outside the home.

Thus, the pandemic created contexts of vulnerability in which the rights of young and adolescent girls might be violated. “Girls and women are always asked to do the housework, and if we don’t do it, we’re punished”, commented Lixiana, a 17-year-old girl in Nicaragua. Coral, a 13-year-old girl in the Dominican Republic, added that “I hope we’ll be able to get back to normal so we can go to school, and my life will be like it used to be. I see a lot of girls who have to do more work at home than the boys” (El Telégrafo, 2021). Thus, the time that young and adolescent girls —especially mothers— dedicate to studying is being affected not only by the school closures, but also by the increase in domestic chores and care work and the rise in psychological, physical and sexual violence (ECLAC/UNICEF, 2020; UNESCO/UN-Women/Plan International, 2020).

VI. Conclusions and recommendations

The pandemic has clearly implied educational declines and losses that have not affected all students equally, resulting in an increase in the education gaps. This report recommends that any of the proposals made here should start with ensuring the reopening of all schools as soon as possible.

Additionally, the challenges and opportunities faced by students and teachers in the transition to remote online education provide valuable perspective for the creation and implementation of education policies in the coming years. This will be very helpful since online distance education is clearly here to stay, given that physical distancing and the prevention of contagion will continue to be a priority over the next several months. We therefore present the following recommendations.

- Rethink hybrid teaching and flexible education modalities

One of the upcoming challenges that the region will have to address is the transition to high-quality hybrid education, taking advantage of advances in digitization to facilitate the gradual return to in-person classes and, more permanently, to extend coverage and increase flexibility as needed in some contexts. As the region moves towards a new normal, education will certainly have to combine in-person and remote modalities to meet the needs of students and comply with health measures. This presents an opportunity to personalize education and rethink teaching and evaluation systems. For example, collaborative teaching spaces could be created where teachers can explore teaching strategies that guarantee a higher degree of learning, motivation, and participation on the part of the students. Another important factor is that the pandemic has caused an increase in school dropout in the region. Therefore, it is also necessary to rethink and implement flexible education modalities that support the reintegration of students into the education system. These flexible education modalities should be easily accessible to diverse and vulnerable populations that have difficulty participating in the traditional education system or that dropped out of school during the pandemic.

- Stimulate the development of socioemotional skills

The development of socioemotional skills in students should be prioritized as a fundamental part of the education process in schools. These skills not only facilitate continuous learning but also allow youths to develop the necessary resilience and flexibility to navigate uncertain contexts and face accelerated environmental and technological changes. In a world that is increasingly focused on remote education and work, the space for developing these abilities is diminished. Therefore, distance learning modalities must include in-person activities (hybrid education formats), because it is very hard to foster the development of coexistence and empathy in a virtual environment.

- Emphasize integral education

The curriculum design should favour the integral formation of students through the inclusion of art, ethics, science, technology, and social skills. It is also important to recognize that the new generations are going to demand new lifestyles and coexistence with the environment. Therefore, students’ opinions must be taken into account in the design of new school curricula. This will not only allow the schools to address issues that are important to students, but it will also give youths a greater role in their educational trajectories. The consideration of all these issues will support the development of a broad, interdisciplinary education.

- Facilitate access to and use of technology through digital training programmes

It will be crucial to facilitate access to the Internet and technological devices and to promote their use at the national level, in order for hybrid education to be accessible to everyone. Training campaigns should also be implemented to help teachers and students develop the necessary digital skills to make good use of the technologies in academic and professional settings. Given that students in rural areas and in vulnerable contexts usually have less access to these technologies, it is important to prioritize the implementation of these programmes in these areas to close the digital and educational gaps.

- Support, promote and protect the mental health of students and teachers

The pandemic also revealed the importance of implementing measures that help monitor the mental and emotional wellbeing of students and teachers and that provide the necessary psychological support for successful educational trajectories. When youths face frequent or prolonged adversity without adequate support, the consequences can affect their cognitive development and their long-term learning capacity.

- Strengthen collaboration between family members and teachers

The educational formats implemented during the pandemic demonstrated the importance of collaboration and empathy between family members and teachers for students’ educational trajectories. Communication between school and home is necessary for maintaining the planned teaching activities, since it allows the work to be monitored from home. This gives teachers a better view not only of students’ progress but also of any difficulties they may be experiencing. Similarly, this collaboration allows schools to identify the challenges that families are facing so as to provide them with tools or support to help them be more involved in their children’s learning process.

- Strengthen cooperation among countries to face the education crisis

The heterogeneity of Latin America and the Caribbean creates opportunities for cooperation among countries to face the challenges of the education crisis. Just this past year, the World Bank highlighted the work of the Mexican university Tec de Monterrey in adapting its educational model, Tec21, to face the COVID-19 pandemic. The model has four main pillars: challenge-based learning; flexibility in how, when and where students learn; a memorable university experience; and inspired professors (Tecnológico de Monterrey, 2021). The lessons from this initiative are valuable for all educational establishments and for students of all ages in the region. Thus, establishing a much more productive, proactive and future-oriented cooperation could contribute to replicating a country’s successful models throughout the region and thereby reducing the existing gaps and overcoming the education crisis.

The pandemic has inarguably caused significant education losses in the region. However, the current crisis can also represent an opportunity to transform education in Latin America and the Caribbean. If managed well, this crisis could generate more inclusive and effective education systems that are better prepared for digitization and the future. It is crucial for countries in the region to work together in order to improve education for Latin America and the Caribbean. If the crisis is not used as an opportunity, then the worrisome social, digital and cognitive gaps will inevitably deepen in the coming years.

Bibliography

Acosta, F. (2021), “Diversificación de la estructura de la escuela secundaria y segmentación educativa en América Latina”, Project Documents (LC/TS.2021/106), Santiago, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), May. Available [online] https://www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/47211-diversificacion-la-estructura-la-escuela-secundaria-segmentacion-educativa.

Acosta, F. and others (2021), “Las políticas para la escuela secundaria en términos de una nueva cuestión social: análisis comparado de casos recientes en Europa y América Latina (Cono Sur)”, Políticas educativas: una mirada internacional y comparada, Monterrey, Escuela Normal Miguel F. Martínez/Sociedad Mexicana de Educación Comparada.

Braslavsky, C. (2001), La educación secundaria: ¿cambio o inmutabilidad? Análisis y debate de procesos europeos y latinoamericanos contemporáneos, Buenos Aires, Santillana.

Castro, M. E., J. H. González Reyes and D. E. Vergara Lozada (2021), “Diversificación de la estructura de la escuela secundaria y segmentación educativa en América Latina: la experiencia de adolescentes y jóvenes en México”, Project Documents (LC/TS.2021/5082), Santiago, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), May. Available [online] https://www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/46860-diversificacion-la-estructura-la-escuela-secundaria-segmentacion-educativa.

Drees-Gross, F. and P. Zhang (2021), “Less than 50% of Latin America has fixed broadband. Here are 3 ways to boost the region’s digital access”. Available [online] https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/07/latin-america-caribbean-digital-….

ECLAC (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean) (2021), “The recovery paradox in Latin America and the Caribbean Growth amid persisting structural problems: inequality, poverty and low investment and productivity”, COVID-19 Special Report, No. 11, Santiago, July. Available [online] https://www.cepal.org/en/publications/47059-recovery-paradox-latin-america-and-caribbean-growth-amid-persisting-structural.

___ (2020), “Universalizing access to digital technologies to address the consequences of COVID-19”, COVID-19 Special Report, No. 7, Santiago, August. Available [online] https://www.cepal.org/en/publications/45939-universalizing-access-digital-technologies-address-consequences-covid-19.

ECLAC/PAHO (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean/Pan American Health Organization) (2021), “The prolongation of the health crisis and its impact on health, the economy and social development”, COVID-19 Report, Santiago, October. Available [online] https://www.cepal.org/en/publications/47302-prolongation-health-crisis-….

ECLAC/UNESCO (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean/United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) (2020), “Education in the time of COVID-19”, COVID-19 Report, Santiago, August. Available [online] https://www.cepal.org/en/publications/45905-education-time-covid-19.

ECLAC/UNICEF (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean/United Nations Children’s Fund) (2020), “Violence against children and adolescents in the time of COVID-19”, COVID-19 Report, Santiago, December. Available [online] https://www.cepal.org/en/publications/46486-violence-against-children-a….

___ (2016), “The right to free time in childhood and adolescence”, Challenges, No.19, Santiago, August. Available [online] https://www.cepal.org/en/publications/40760-right-free-time-childhood-a….

ECOSOC (United Nations Economic and Social Council) (2011), Challenges for Education with Equity in Latin America and the Caribbean, Buenos Aires, May. Disponible [en línea] https://www.un.org/en/ecosoc/newfunct/pdf/6.challenges.for.education.wi….

Educar Chile (2020), “Informe de resultados Encuesta #VinculandoAprendizajes: indagación sobre estrategias de los docentes y apoyos requeridos para la educación a distancia en contexto de crisis sanitaria”, Santiago, June. Available [online] https://www.educarchile.cl/sites/default/files/2020-06/VinculandoAprend….

Elacqua, G., L. Marotta and C. Méndez (2020), “Covid-19 y desigualdad educativa en América Latina”, El País, 11 October. Available [online] https://elpais.com/planeta-futuro/2020-10-11/covid-19-y-desigualdad-edu….

El Telégrafo (2021), “Pandemia amplía brecha en educación de las niñas”, 22 July. Available [online] https://www.eltelegrafo.com.ec/noticias/mundo/8/pandemia-educacion-ninas.

García Jaramillo, S. (2020), “COVID-19 and primary and secondary education: the impact of the crisis and public policy implications for Latin America and the Caribbean”, COVID 19-Policy Documents Series, No. 20, United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), New York, August.

González, A. M. and M. González (2021), “Diversificación de la estructura de la escuela secundaria y segmentación educativa en América Latina: la experiencia de adolescentes y jóvenes en Costa Rica”, Project Documents (LC/TS.2021/7888), Santiago, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), July. Available [online] https://www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/47040-diversificacion-la-estruct….

Guedes, A. and others (2016), “Bridging the gaps: a global review of intersections of violence against women and violence against children”, Global Health Action, vol. 9, No. 1, June. Available [online] 10.3402/gha.v9.31516.

IIPE-UNESCO (UNESCO International Institute for Educational Planning)(2019), Desafíos de la educación secundaria en América Latina. Buenos Aires: IIEP-UNESCO Office for Latin America. Available [online] https://es.unesco.org/news/desafios-educacion-secundaria-america-latina.

López, N. and J. Tedesco (2002), “Challenges for secondary education in Latin America”, CEPAL Review, No. 76 (LC/G.2175-P), Santiago, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), April. Available [online] https://www.cepal.org/fr/node/28195.

Ministry of Education of Chile/Centro de Estudios (2020), Impacto del COVID-19 en los resultados de aprendizaje y escolaridad en Chile: análisis con base en herramienta de simulación proporcionada por el Banco Mundial, Santiago, August. Available [online] https://bibliotecadigital.mineduc.cl/handle/20.500.12365/14663.

Moncada Godoy, G. E. and K. Y. Rivera Reyes (2021), “Diversificación de la estructura de la escuela secundaria y segmentación educativa en América Latina: la experiencia de adolescentes y jóvenes en Honduras”, Project Documents (LC/TS.2021/140), Santiago, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), November. Available [online] https://www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/47419-diversificacion-la-estruct….

Neidhöfer, G., N. Lustig and M. Tommasi (2021), “Intergenerational transmission of lockdown consequences: prognosis of the longer-run persistence of COVID-19 in Latin America”, The Journal of Economic Inequality, No. 19, July.

Núñez, P., V. Seca and V. Arce (2021), “Diversificación de la estructura de la escuela secundaria y segmentación educativa en América Latina: la experiencia de adolescentes y jóvenes la Argentina”, Project Documents (LC/TS.2021/4572), Santiago, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), April. Available [online] https://www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/46818-diversificacion-la-estructura-la-escuela-secundaria-segmentacion-argentina.

Patiño, I. and J. Campi-Portaluppi (2021), “Diversificación de la estructura de la escuela secundaria y segmentación educativa en América Latina: la experiencia de adolescentes y jóvenes en el Ecuador”, Project Documents (LC/TS.2021/107113), Santiago, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), September. Available [online] https://www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/47207-diversificacion-la-estructura-la-escuela-secundaria-segmentacion-ecuador.

Rieble-Aubourg, S. and A. Viteri (2020), “CIMA Brief #20: Are we prepared for online learning?”, Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), April. Available [online] https://publications.iadb.org/en/cima-brief-20-covid-19-are-we-prepared….

Rivero, L. and D. Viera (2021), “Diversificación de la estructura de la escuela secundaria y segmentación educativa en América Latina: la experiencia de adolescentes y jóvenes en el Uruguay”, Project Documents (LC/TS.2021/4668), Santiago, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). Available [online] https://www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/46814-diversificacion-la-estruct….

Seusan, L. and R. Maradiegue (2020), Education on hold: a generation of children in Latin America and the Caribbean are missing out on schooling because of COVID-19, Panama, United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), November. Available [online] https://www.unicef.org/lac/informes/educacion-en-pausa.

SUMMA (2020), Docencia durante la crisis sanitaria: la mirada de los docentes. ¿Cómo están abordando la educación remota los docentes de las escuelas y liceos de Chile en el contexto de la crisis sanitaria?, Santiago, May. Available [online] https://www.miradadocentes.cl/Informe-de-Resultados_Docencia_Crisis_Sanitaria.pdf.

Tecnológico de Monterrey (2021), “Adaptación educativa del TEC ante pandemia: elogiada por Banco Mundial”, November. Available [online] https://tec.mx/es/noticias/nacional/institucion/adaptacion-educativa-de….

Trucco, D. (2014), “Educación y desigualdad en América Latina”, Social Policy series, No. 200 (LC/L. 3846), Santiago, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), June. Available [online] https://repositorio.cepal.org/handle/11362/36835.

Turkewitz, J. (2021), “1+1=4? Latin America confronts a pandemic education crisis”, The New York Times, June. Available [online] https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/26/world/americas/latin-america-pandemic-education.html.

UNESCO/UN-Women/Plan International (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization/United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women/Plan International) (2020), “Educación, género y COVID-19: consecuencias para niñas y adolescentes”. Available [online] https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.in….

UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund) (2021), “114 million children still out of the classroom in Latin America and the Caribbean”, March. Available [online] https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/114-million-children-still-out-cl….

___ (2020), “The impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of adolescents and youth”. Available [online] https://www.unicef.org/lac/en/impact-covid-19-mental-health-adolescents….

Urdan, T. and F. Pajares (eds.) (2006), Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Adolescents, Connecticut, Information Age Publishing.

World Bank (2021), Acting now to protect the human capital of our children: the costs of and response to COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on the education sector in Latin America and the Caribbean, Washington, D.C, March.

[1] The interviews considered in this article were conducted in 2020 as part of the second phase of a study by ECLAC, UNESCO International Institute for Educational Planning (IIPE) and UNICEF LACRO, with support from Norway. The interviews with students, teachers, and parents in the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela and Chile were held between March 2021 and April 2021. See Castro, González Reyes and Vergara Lozada (2021); González and González (2021); Moncada Godoy and Rivera Reyes (2021); Núñez, Seca and Arce (2021); Patiño and Campi-Portaluppi (2021); and Rivero and Viera (2021). To maintain confidentiality, the names used in the text are fictitious.

[2] Uruguay has fairly low secondary education coverage rates relative to the regional average.