Nearly 30% of Young Latin American Women Have Been Teenage Mothers

Work area(s)

Comprehensive sex education and sexual and reproductive health services should be a priority in youth-oriented public policies, a study by ECLAC emphasizes.

(November 13, 2014) Nearly 30 % of young women in Latin America become mothers before 20 years of age and the majority of them are socioeconomically underprivileged, which fosters the intergenerational reproduction of poverty, hinders women’s autonomy and their life projects, and underscores the need for sex education and reproductive health services to be made a public policy priority, according to a new report by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC).

The study Reproduction in adolescence and its inequalities in Latin America (only available in Spanish), published recently, indicates that the teenage maternity rate—which shows the number of mothers 15 to 19 years old versus the total number of women that same age—declined in the region between 2000 and 2010, after having increased between the censuses of 1990 and 2000.

The proportion of 19 and 20 year olds in Latin America who were already mothers fell to about 28 % in 2010 from 32 % in 2000, which is similar to the level seen in 1990 (29 %).

Looking at the figures for girls and women between 15 and 19 years of age, which includes youth who have not lived through their entire adolescence, the percentage fell to 12.5 % in 2010 from 14.0 % in 2000. Nonetheless, in the first decade of this century the decline in teenage maternity was much smaller than that of total fertility and it did not counteract the increase from the 1990s, which means that this indicator is currently almost the same as it was 20 years ago.

The study analyzes available country data using five suppositions on the different possible meanings of no response to the question about children having been born alive.

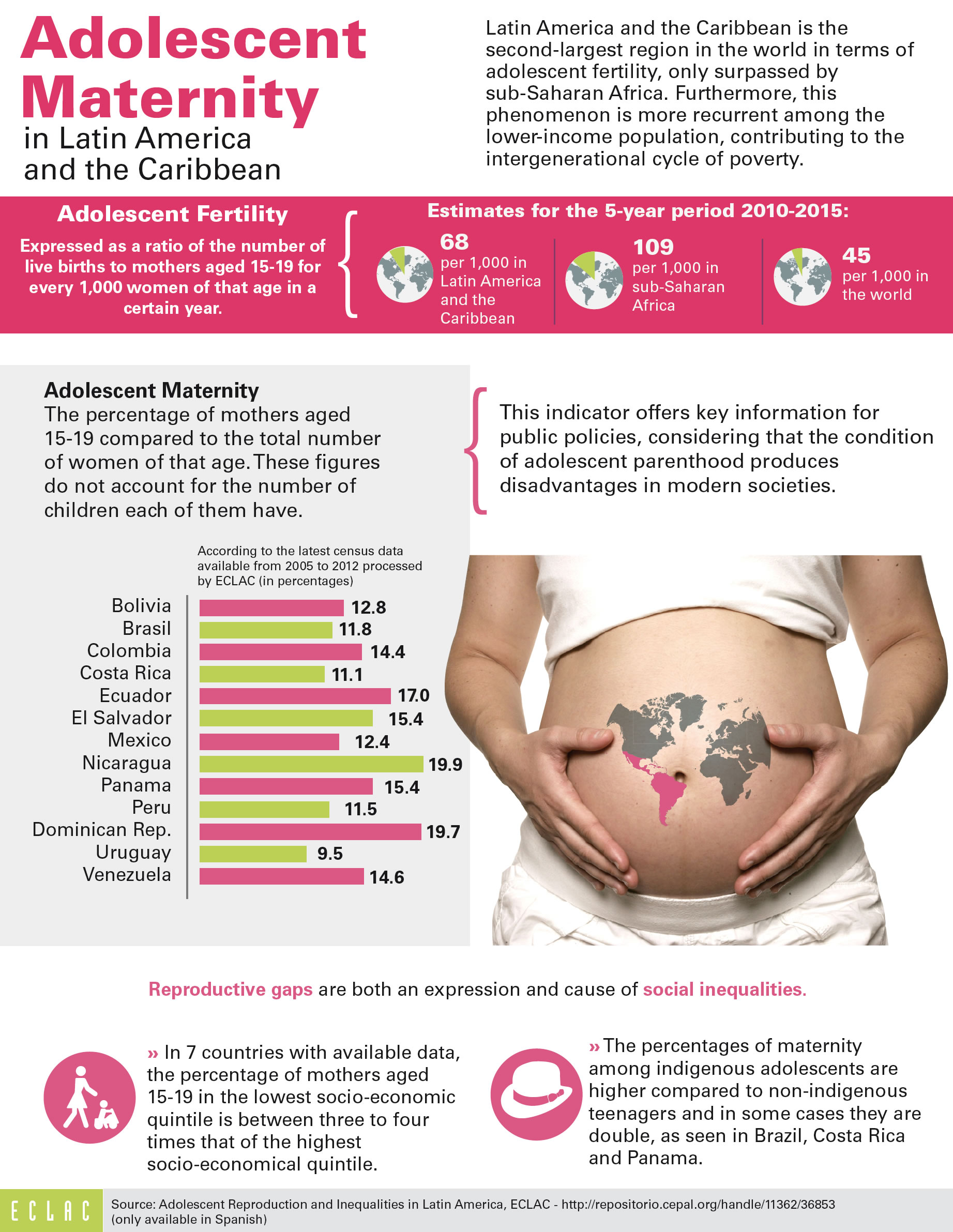

In the scenario where the lack of a response is attributed to women having no children who were born alive, the countries with the greatest maternity rates in women from 15 to 19 years of age are Nicaragua (19.9 %), the Dominican Republic (19.7 %) and Ecuador (17.0 %), while the lowest levels are seen in Uruguay (9.5 %), Costa Rica (11.1 %) and Peru (11.5 %). All the countries have rates that are far above those seen in Western Europe, where adolescent maternity is around 2 %.

In addition, for the first time indicators are being released on maternity among girls below 15 years of age. Although the levels do not exceed 0.5 %, it is worrisome that this trend is on the rise because of the extreme vulnerability of such young mothers.

Meanwhile, the number of children that women have throughout their lifetime (reproductive intensity) has fallen among all social groups, but the age at which they have their first child (the reproductive calendar) continues to be quite early, especially in lower socioeconomic strata, which contributes to the intergenerational reproduction of poverty.

This early start to maternity is reflected in the fact that nearly 17.5 % of all infants in Latin America and the Caribbean are born to adolescents, a rate that is higher than that of Sub-Saharan Africa (15 %) and the global average (11.2 %).

In seven countries with available data, the number of mothers between 15 and 19 years of age in the lowest socioeconomic quintile is between three and four times greater than that of the highest quintile.

Another line of research indicates that in seven countries under analysis, more than half of the adolescents with low schooling levels are adolescent mothers. Meanwhile, the maternity rate among indigenous adolescents is higher than that of non-indigenous youth.

Regarding the adolescent fertility rate, which is the traditional indicator for comparing adolescents and is included in target 5.B of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), Latin America and the Caribbean registers 68 births among mothers 15 to 19 years old for every 1,000 women of the same age—a rate that is surpassed only by Sub-Saharan Africa, which has 109 out of every 1,000, according to figures from 2010.

The region also stands out for having the second-smallest decline in adolescent fertility (-12.9 %) in the last 20 years, after Sub-Saharan Africa (-6.1 %).

With regard to that, the report notes that the adolescent fertility rate is higher and its reduction is slower than what one would expect considering the sharp and sustained fall in total fertility as well as improvements in social indicators, particularly those related to education and health, which rank above the average seen in developing countries.

The study concludes that public policies in this area, as the Montevideo Consensus on Population and Development contends and as the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) has emphasized numerous times, should include comprehensive sex education, counseling for young women to exercise their rights and make informed decisions, and access to sexual and reproductive health services that include the provision of birth-control methods.

ECLAC also warns that, due to a lack of opportunities, barriers to personal projects and cultural patterns, many girls see maternity as a way out of poverty, which underscores the need to strengthen policies on education and labor market insertion to expand their development possibilities.

More information at www.cepal.org.

Related content

Adolescent Maternity in Latin America and the Caribbean

Latin America and the Caribbean is the second-largest region in the world in terms of adolescent fertility, only surpassed by sub-Saharan Africa. Furthermore, this phenomenon is more recurrent among…

Country(ies)

- Latin America and the Caribbean

Contact

Public Information Unit

- prensa@cepal.org

- (56 2) 2210 2040