Early childhood in post-pandemic Latin America and the Caribbean

Work area(s)

Topic(s)

Raquel Santos Garcia

Social Affairs Officer of ECLAC

Introduction

The evidence is that children in early childhood years (aged 0 to 8), having spent at least half their lives in a context of health emergency, will face severe consequences for their development and learning opportunities. This crisis has had a devastating impact on multiple aspects of children’s lives. First, many have experienced the loss of parents, caregivers and loved ones, as well as contracting the disease themselves and being left with the after-effects. The economic crisis has also led to a sharp increase in poverty in many households, which has affected children’s quality of life. Lastly, and more broadly, the lockdowns and other restrictions applied to contain the pandemic affected children’s ability to attend educational institutions, socialize with peers and family members they did not reside with and receive the health care they were entitled to.

Negative effects on cognitive, linguistic, and motor development have been observed as a result, especially in children from poor families and those whose financial situation worsened as a result of the pandemic. This unprecedented situation also affected children’s emotional well-being and health, leading to increased levels of anxiety and irritability, as well as higher rates of malnutrition and new epidemiological risks as a result of them not receiving the vaccines they were due, among other factors (ECLAC, 2022; ECLAC/UNICEF, 2021; UNICEF, 2023a.

The effects of the pandemic came on top of existing challenges, such as the markedly disproportionate incidence of poverty among children. Before coronavirus, in 2019, 11.4% of the region’s total population lived in extreme poverty, while 13.1% of children and adolescents aged between 0 and 17 were in this situation. In 2021, the gap increased from 1.7 to 5.1 percentage points (ECLAC, 2023). Social protection divides also widened, with cutbacks in social policy investment for children, increasing the risks of intergenerational transmission of poverty (ECLAC, 2022). Figures for 2023 indicate that while 29% of the population of Latin America and the Caribbean is poor, this figure rises to 42.5% if only children and adolescents aged between 0 and 17 are considered (ECLAC, 2023).

Comprehensive child development policies have profound and immediate impacts on children’s lives and on the whole of society. During this early stage of the life cycle, the brain adapts and develops particularly quickly, enabling children to acquire cognitive, emotional and linguistic skills that will influence their long-term development. The quality of interpersonal interactions, access to nurturing environments and appropriate stimulation during the early years are crucial in establishing fundamental neuronal connections that will underpin their life paths (Center on the Developing Child, 2007). It has been shown, for example, that investment in quality early childhood education is crucial in ensuring healthy development and improved opportunities for success in adulthood, including educational and employment pathways and quality of life. Moreover, this investment generates a higher return than any other, contributing cost-effectively to a country’s development (Heckman, 2013).

Likewise, children who face structural inequalities, whether owing to their ethnicity or race, socioeconomic status, territory of origin, gender, or risk factors such as violence, food insecurity or lack of access to water and sanitation, health services or education, all of which were aggravated and entrenched during the pandemic, face challenges from an early age in accessing future educational and employment opportunities, which perpetuates the cycle of inequalities. The idea that children only need looking after has evolved into a view that societies should foster and facilitate their all-round development, ensuring conditions of good health, adequate nutrition, protection and security, early learning and responsive care that, as posited by the “nurturing care” framework, create a solid foundation for their development (PAHO/UNICEF/World Bank, 2021).

The Convention on the Rights of the Child, adopted in 1989 by the United Nations General Assembly and ratified by all countries of the region (United Nations, 1989), has been influential in transforming the way the international community and decision-makers perceive early childhood development. By recognizing children as rights holders and promoting a comprehensive approach to their well-being, with special attention to their right to health and education, it highlights the vital need to ensure optimal cognitive, emotional and social development. The Convention also underscores the importance of the early years of life and has led to the adoption of specific instruments that have increased the global visibility of comprehensive early childhood care in the last two decades. Examples are General Comment No. 7 (2005) of the Committee on the Rights of the Child (United Nations, 2005) and the World Conference on Early Childhood Care and Education in 2010 (OEI, 2023).

More recently, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have reaffirmed and strengthened the international commitment to ensure an equitable and prosperous future for all children. Many of the SDGs and their targets and indicators focus directly on early childhood.1 So have regional instruments such as the Regional Agenda for Inclusive Social Development (ECLAC, 2020) and the Montevideo Consensus on Population and Development (ECLAC, 2013). These aim to address a wide range of global challenges, including poverty, quality education, gender equality and health, with the aim of creating an enabling environment for the all-round growth and development of children throughout the world.

I. Maternal and child health as a foundation for child development

From a maternal and child health perspective, the first 1,000 days of life, from the start of pregnancy until a child is 2 years old, are vitally important. During this stage, babies’ brains and bodies develop and grow rapidly, laying the foundation for their health and well-being throughout their lives. Good health, adequate nutrition, safety and protection, responsive care and early learning opportunities, which are components of the nurturing care framework (PAHO/UNICEF/World Bank, 2021), are essential factors influencing children’s cognitive, emotional and physical development. During this stage, the effects of poor nutrition or lack of health care, for example, can be permanent, negatively affecting health into adulthood. Moreover, during those first 1,000 days, the mother’s health and well-being have a direct impact on the baby’s health (Castillo and Marinho, 2022).

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed existing weaknesses in Latin American and Caribbean health systems and further exacerbated inequalities in access to health-care services. Chronic underfunding of health systems (which receive less than the regionally agreed 6% of GDP), lack of access to quality services, shortages of medical resources, high out-of-pocket spending and coordination difficulties, coupled with the disruption of health services, limited the provision of adequate care to women of reproductive age and children in their first years of life. Until mid-2021, most of the countries of Latin America and the Caribbean faced disruptions to health services, from primary to the most complex levels of care, because of pandemic containment measures. Even after the most critical and uncertain period of the crisis, many of the countries continued to report reduced coverage, including for newborn care, family planning, prenatal and postnatal services, childbirth care, treatment of infectious and non-communicable diseases, and vaccination campaigns (UNICEF, 2021). These factors have been compounded by a possible change in the behaviour of the population, with people becoming more reluctant to seek health care during the pandemic (Chmielewska and others, 2021). The pandemic has also led to a worsening of key maternal and child health indicators, particularly for maternal mortality, chronic malnutrition and the prevalence of children who have not been vaccinated or whose immunization schedules are incomplete.

A. The maternal mortality ratio was set back by a decade

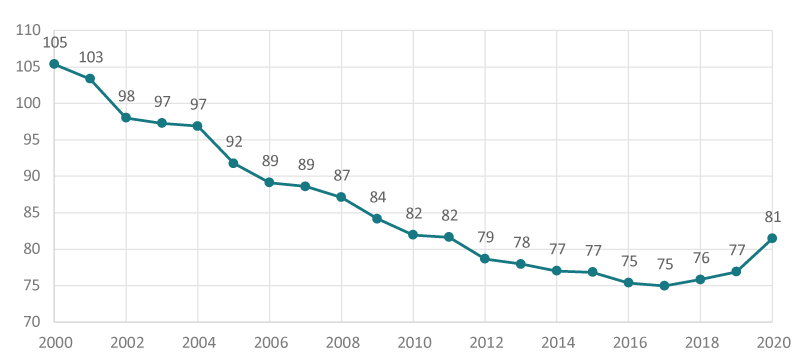

It is estimated that, owing to the pressure the crisis put on health services, one third of pregnant women who contracted COVID-19 did not receive adequate medical care (Maza-Arnedo and others, 2022). In addition, maternal mortality, after steadily declining in recent decades, has stagnated in recent years and actually increased significantly in 2020. Regional figures for 2020 are comparable to those of a decade ago (see figure 1). Latin America and the Caribbean is the only region in the world not to have shown sustained progress on this indicator. The situation is disturbing given that most maternal deaths are avoidable, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), as there are widely known prevention and treatment measures for complications during pregnancy, childbirth and the 42 days that follow (Marinho, Dahuabe and Arenas de Mesa, 2023). This has a significant impact on the physical and mental health of children, including the impact that being orphaned has on their life paths.

Figure 1

Latin America and the Caribbean (31 countries): maternal mortality ratio, 2000–2020

(Number of deaths per 100,000 live births)

Source: Prepared by the author on the basis of M. L. Marinho, A. Dahuabe and A. Arenas de Mesa, “Salud y desigualdad en América Latina y el Caribe: la centralidad de la salud para el desarrollo social inclusivo y sostenible”, Social Policy series, No. 244 (LC/TS.2023/115), Santiago, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), 2023.

The effects of the pandemic also include increases in maternal depression (Chmielewska and others, 2021). In the area of nutrition, research in low- and middle-income countries shows a significant increase in maternal anaemia and the proportion of pregnant women with a low body mass index, affecting the nutrition of the generation born in this period (Osendarp and others, 2021).

B. Child malnutrition: an unyielding situation

Malnutrition in the early years of life can lead to irreversible physical and cognitive disabilities. The COVID-19 pandemic has altered consumption patterns, particularly affecting the most vulnerable households and exacerbating the double burden of undernutrition and overweight-obesity. Despite recommendations for healthy eating and exclusive breastfeeding in the first six months of life, ECLAC/FAO (2020) research shows that people from lower-income households in particular (World Bank/UNDP, 2021) have tended to consume less nutritious and cheaper diets with less fresh food, sometimes even skipping meals. Among other factors, this is due to the reduction in regular health check-ups, the decline in newborn care services, reduced coverage of school meal programmes and the worsening economic crisis (ECLAC, 2022 and 2021; Castillo and Marinho, 2022).

Similarly, studies in low- and middle-income countries have identified a higher incidence of malnutrition and nutrient deficiencies in vulnerable groups, such as those with low incomes and lower levels of education (Black and others, 2013; Restrepo-Méndez and others, 2015). These findings, combined with changes in consumption, suggest an increased risk of malnutrition in children under 5 years of age in vulnerable households during the pandemic. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2023 (FAO and others, 2023) emphasizes that the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on malnutrition have yet to be fully revealed.

In most countries of the region, chronic child undernutrition has gradually declined over the last decade.2. Even before the pandemic, however, this decline was too slow for SDG target 2.2 to be met. The proportion of children under 5 years of age with chronic undernutrition is estimated to have averaged 11.5% in 2022, compared to 12.7% in 2012. At the same time, progress regarding children with low birth weight has stalled, with the proportion remaining unchanged (9.5% in 2012 and 9.6% in 2022). As for overweight, the data indicate an increase, so that the target is receding: the prevalence of overweight children rose from 7.4% in 2012 to 8.6% in 2022 (FAO and others, 2023).

C. The largest setback for routine childhood immunization in 30 years

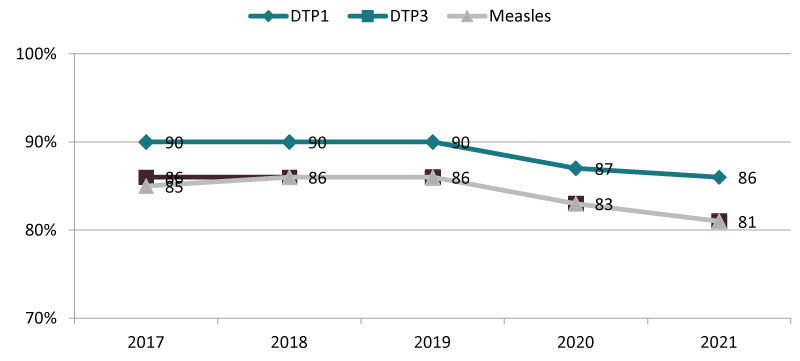

UNICEF (2023a) has reported that the COVID-19 pandemic had a disastrous impact on childhood immunization worldwide. Immunization coverage in Latin America and the Caribbean has fallen over the past five years, with particularly large declines since the pandemic. The coverage of diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis (DTP) and measles vaccination has declined sharply, resulting in an increase in the prevalence of “zero-dose” and undervaccinated3 children in the region.

Although the regional figures for the prevalence of vaccinated children were similar to or higher than the global figures in 2017, figure 2 shows a significant drop relative to the global average for DTP vaccination (4 percentage points for the first dose and 6 percentage points for the full three-dose schedule), even though the global average also declined (see figure 2A). From 2017 to 2021, for example, the number of children in the region without any vaccine doses nearly quadrupled from 5% to 18% (see figure 2B). It is estimated that nearly 1.8 million children will not be vaccinated and another 650,000 are undervaccinated in the region (UNICEF, 2023a).

Social determinants of health play an important role in immunization. Although territory does not appear to be a determining factor in the prevalence of zero-dose children, children from the poorest households are almost three times as likely to have received no doses of DTP as children from the richest households. Similarly, the prevalence of zero-dose children decreases as the mother’s level of education rises (UNICEF, 2023a).

Figure 2

Prevalence of children who have received the DTP1, DTP3 and measles vaccines in the world and in Latin America and the Caribbean, and of zero-dose and undervaccinated children in Latin America and the Caribbean

A. World and Latin America and the Caribbean: prevalence of children who have received the DTP1, DTP3 and measles vaccines, 2017–2021

(Percentages)

|

World  |

Latin America and the Caribbean  |

B. Latin America and the Caribbean: prevalence of zero-dose and undervaccinated children, 2000–2021

(Percentages)

Source: United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), The State of the World’s Children 2023: For every child, immunization, UNICEF Innocenti – Global Office of Research and Foresight, Florence, 2023.

The COVID-19 pandemic brought out existing weaknesses in health-care systems. Critical indicators such as maternal mortality and vaccination coverage have regressed markedly, with disproportionate effects on the most vulnerable sectors of the population. Social determinants, including income level and maternal education, play a crucial role in shaping these health problems. Multisectoral initiatives and programmes that address children’s and mothers’ living conditions play a fundamental role in safeguarding their overall health and well-being and are crucial for dealing with persistent health inequalities (Marinho, Dahuabe and Arenas de Mesa, 2023).

II. Identifying opportunities to ensure quality education from the earliest years of life

In recent decades, early childhood care and education (ECCE) has come to the fore as the importance of learning in the early years of life has been recognized. This has had a significant impact on formal education, careers, incomes, autonomy and the social and productive development of society (ECLAC, 2022). Advances in neuroscience and positive evidence for the benefits of quality early childhood programmes, coupled with a rights-based approach, have prompted governments around the world to expand access to ECCE programmes.

The SDGs include an explicit focus on early childhood education, as reflected in their target 4.2, which calls for universal access for all girls and boys to early childhood development, care and pre-primary education so that they are ready for primary education. Two significant milestones in the protection of ECCE rights were the Buenos Aires Declaration in 2017 and the Tashkent Declaration, signed in November 2022, both reaffirming the universal and fundamental nature of the right to education from birth (UNESCO, 2022).

Legal and institutional reforms and a significant increase in financing have driven remarkable advances in access to early childhood education in Latin America and the Caribbean over recent decades. In 2006, 37.1% of children under the age of 6 attended pre-primary education, a figure that had risen to 46.6% by 2020. Attendance one year before the official primary school starting age was almost universal (94.5% and 94% for girls and boys, respectively), with territorial and income gaps having narrowed considerably (UNESCO/UNICEF/ECLAC, 2022; ECLAC, 2022).

Early in the pandemic, too little attention was paid to education: schools were among the first establishments to close and among the last to reopen. This lack of prioritization in a region marred by multiple inequalities has the potential to worsen existing inequalities in the medium and long term and leave new generations with a “scar effect” (ECLAC, 2022).

Similarly, early childhood learning activities were often restarted without adequate planning or national coordination. Children of the age to attend ECCE programmes have been among the most affected by the school closures: it was the level with the largest drop in attendance during the early years of the pandemic, and the one where attendance rates are now furthest below those of 2019.

A. Young children have been most affected by the remote education arrangements put in place during the pandemic

School closures had a direct effect on access conditions for education, affecting some groups severely: the impact was especially strong for children under 3 years old and in low-income households, widening the gaps that characterize the education system. Even when face-to-face attendance was gradually implemented in combination with often rigorous health protocols, families were reported to be reluctant to send their children to school for fear that they were not safely and adequately prepared to receive the education community.

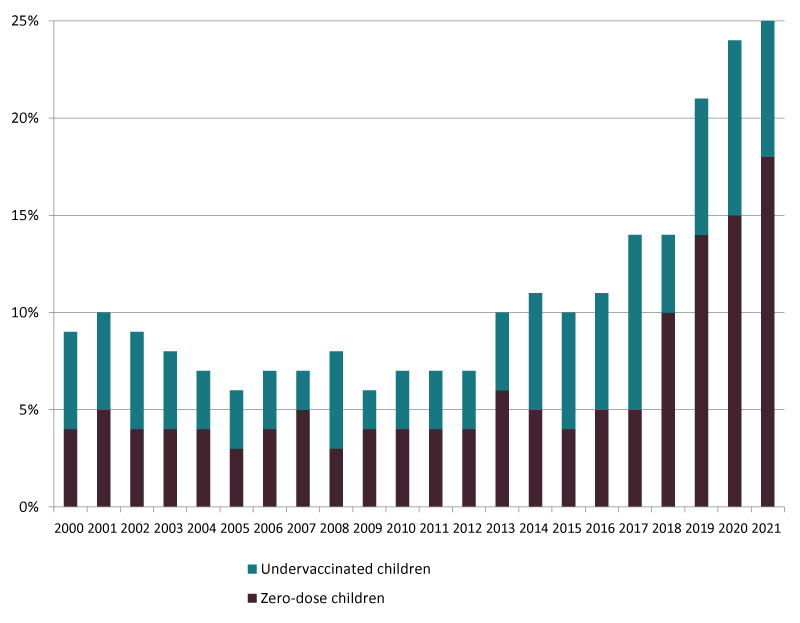

Of all education levels, the negative impacts on school attendance have been most evident at the pre-primary stage. If children one year younger than the official primary school starting age4 are considered, attendance rates fell by 6.1 percentage points between 2019 and 2020 (from 94.5% to 88.4%) and by almost 8 points between 2019 and 2021 (86.8%). If the age group is extended to those three years younger than the official primary school starting age, i.e. children from 3 to 5 years old, the reduction was from 73.9% to 68.1% between 2019 and 2021 (5.8 percentage points) (see figure 3). For the other education levels, no significant drops were observed during the pandemic (ECLAC, 2022).

Figure 3

Latin America (14 countries):a: attendance rates among children below the official primary school starting age, 2019–2022

(Percentages)

Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), on the basis of the Household Survey Data Bank (BADEHOG).

a Weighted averages estimated from information on the following countries: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Plurinational State of Bolivia and Uruguay.

b Weighted averages estimated from information on the following countries: Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Mexico, Peru and Uruguay.

As of 2022, neither of these two age groups had returned to pre-pandemic attendance levels. If children one year younger than the official primary school starting age are considered, the gap between 2019 and 2022 was almost 2 percentage points (94.5% and 92.6%, respectively). For the broader age group, i.e., those up to three years younger than the primary school starting age, the gap between these two periods was 2.4 percentage points, with a decline from 73.9% to 71.5%.

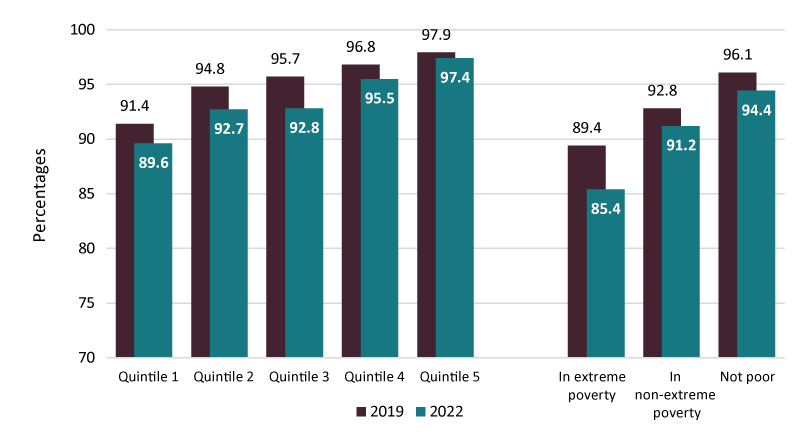

The most striking figures are observed, however, when the information is broken down by household income. While the highest-income quintile was close to recovering pre-pandemic attendance levels, with a difference of just 0.5 percentage points and a level of access that was still near-universal (97.9% in 2019 and 97.4% in 2022), the middle- and low-income quintiles had yet to return to pre-pandemic levels. The gap was significant for the middle-income quintile, with a difference of 2.9 percentage points. For extremely poor households, the difference was 4 percentage points, with a decline from 89.4% to 85.4% between the two periods. This means that the gap between children in extremely poor households and those above the poverty line increased from 6.7 to 9 percentage points between 2019 and 2022 (see figure 4).

Figure 4

Latin America (14 countries):a pre-primary attendance rate among children one year younger than the primary school starting age, by per capita income quintile and poverty status, around 2019 and 2022

(Percentages)

Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), on the basis of the Household Survey Data Bank (BADEHOG).

a Weighted averages estimated from information on the following countries: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Plurinational State of Bolivia and Uruguay.

A survey conducted by ECLAC and UNICEF5 among ministries of education or ministries of social development and UNICEF country offices in the region found that the distance learning model was particularly challenging for the youngest age groups, as they are more dependent on family members or caregivers to use electronic devices. Furthermore, in competing with other children and adolescents in the same household for remote education, young children were often given lower priority for access to devices and the Internet when other family members also needed them. These challenges came on top of cross-cutting issues related to remote education, such as divides in access to digital devices and limited connectivity.

In a context of economic crisis and fiscal constraints, the countries were forced to change their priorities to cope with the immediate demands of the health emergency. This included the creation of new educational materials for primary and secondary schools. As a result, the budget for early childhood education decreased overall. Of the 12 countries with disaggregated government expenditure data for this level of education, 8 cut their budgets in absolute terms. This decrease can be attributed both to the reorganization of priorities and to the fall in GDP.

For early childhood educators, the pandemic brought new demands to adapt their teaching strategies. These adaptations were often carried out without proper government guidelines or training to adapt the methodology to the context. The emergency also had major impacts on their working conditions, for example by increasing their workload and requiring them to balance classes with domestic and care responsibilities and fund their own teaching resources. In particular, the mental health of educators was a pervasive issue in the region, with 16 of the 26 countries covered by the above-mentioned survey considering it a critical issue.

B. The pandemic brought new perspectives and innovations to the pursuit of quality early childhood care and education

In the region, the pandemic also brought innovations and opportunities for change (ECLAC, 2022), in line with the commitments in the Tashkent Declaration from the World Conference on Early Childhood Care and Education in 2022 (UNESCO, 2022).

1. Diversifying ECCE learning spaces, practices and materials

The closure of educational centres forced early childhood education systems to adapt to the new conditions and design solutions that would provide continuity in education services. Alternative teaching methods catering to specific populations have gained importance, and lessons have been learned from teaching and learning approaches involving more inclusive technologies and media. These include methodologies that adapt the principle of interculturality and the adoption of Indigenous languages in the classroom, in public spaces and in radio and television broadcasting with the aim of enhancing the inclusion of children and involving their families, who often do not speak the official language of instruction. A noteworthy case is Mexico’s “Aprende en Casa” programme, which broadcast its educational content in 15 Indigenous languages. Argentina, Ecuador and the Plurinational State of Bolivia implemented similar programmes. Also important has been individualized or small group teaching, as implemented in Ecuador and the Plurinational State of Bolivia. In Panama, the “Mochila Cuidar” programme provided a kit organized by age group with shape sorter toys, a set of wooden blocks, a ball, jigsaws, crayons, a sketchbook and an activity guide for families who did not have the materials to work with children.

2. Strengthening ECCE staff training and professional development systems

The need to adjust training processes has changed the general perception of online training, so that it is now seen as not only possible but successful. Most countries in the region designed remote training solutions or adapted their initial training programmes. The need to expand distance training led to the creation of participatory methodologies and multiple platforms, which are still available for both initial and ongoing training, thus responding to one of the persistent challenges of ECCE. In addition, the availability of resources and infrastructure, combined with greater societal acceptance of online training, has the potential to open up opportunities for educational agents to train using resources from other countries in the region via South-South cooperation.

Similarly, the issue of early childhood educators’ mental health, which was a challenge even before the pandemic, has gained traction and attention. It was finally recognized that a stable and healthy teaching force is necessary to support children’s development and learning both in times of stability and in periods of crisis or emergencies. This has become a key issue for child development. In Peru, teaching staff were provided with tele-assisted psychological care to help them cope with the changes they were experiencing. In Chile, in collaboration with the Organization of Ibero-American States (OEI), courses on emotional well-being were implemented and the Council for Social Participation and Mental Health in Early Childhood Education was created to develop recommendations for implementation in the coming years.

3. Fostering collaboration between families and educators

Isolation forced families to become implementers of educational strategies with their children and brought their role in children’s educational development into the debate. This led to greater involvement in learning processes, resulting in a sustained, wide-ranging and effective link between educators and families. Families and schools have learned to work collaboratively towards a common goal, with families becoming more aware of the resources available to facilitate learning. The engagement of families has provided a valuable opportunity to recognize the home as an environment conducive to learning.

In Costa Rica and Chile, some television programmes providing training for families and materials produced for them with educational teams have been continued beyond the pandemic. The plan is to carry on with strategies that proved effective during the lockdown period. In relation to the education of children under the care of mothers deprived of their liberty in Paraguay, a special, dedicated effort has been made to ensure the continuity of the educational process for both the mothers and prison professionals. In Chile, lastly, indicators of active participation by parents and caregivers in story reading have been encouraging: between 2019 and 2020, the proportion of caregivers who did not read stories to children decreased from 88.8% to 34.1%, and the proportion who read stories for more than an hour a day increased from 5% to 46.2% (Narea and others, 2021).

In summary, it can be said that more attention has been paid to early childhood education in Latin America and the Caribbean over recent decades. However, the closure of schools triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic presented significant challenges that disproportionately affected young children, diminishing opportunities to address inequalities from an early age. Nonetheless, opportunities did emerge, such as the diversification of teaching strategies and online training for educators. In addition, the importance of educators’ mental health and the involvement of families in children’s learning was highlighted. Collaboration between families and educators was strengthened, with homes recognized as learning environments.

III. Recommendations for comprehensive early childhood development in the post-pandemic period

As has been argued, comprehensive early childhood development is essential if a fairer and more equitable, healthy and productive future is to be built. Despite the efforts made, particularly in the last two decades, to strengthen social policies that focus particularly on this stage of the life cycle, the COVID-19 pandemic was a major shock. The crisis has reconfigured priorities and exacerbated inequalities, leading to major setbacks with social indicators and hampering the push for inclusive social development, a strategic dimension of sustainable development. Latin America and the Caribbean was particularly hard hit, and the needs of young children were largely overlooked.

In a context of recovery from a series of crises, it is imperative to rethink strategies and take decisive and transformative action to reduce the risks of intergenerational transmission of poverty, address inequalities and overcome persistent challenges in the different sectors.

In view of this and of what has been discussed in the previous sections, five areas of attention have been identified as priorities for the comprehensive early childhood development of all children in the region.

A. Translate scientific evidence into sustainable and effective State policies

Despite the overwhelming scientific evidence for the benefits of investing in early childhood, it is worrying to note that this knowledge has not yet spread beyond specialized circles. During the pandemic, the region witnessed a reversal of such investment, as evidenced by declining resources for social policies targeting children, reduced access to social protection and shrinking budgets for ECCE.

Closing the gap between the available evidence and government action is crucial to address the issue. This means, first and foremost, communicating beyond specialist circles, reaching decision-makers, building partnerships with other policy sectors and conveying information effectively and clearly to taxpayers and families with very young children.

Given the need for this investment to be lasting and evaluated over the long term, it is essential to recognize that policies with an overarching State vision need to be implemented in a region characterized by political instability and shifting interests. This means establishing sound legal frameworks to ensure long-term commitment, securing multilateral agreements and agendas such as the Regional Agenda for Inclusive Social Development (ECLAC, 2020), seeking partnerships with key actors in civil society and the private sector, and providing for financial sustainability and access to services, especially at times of crisis and political uncertainty

In addition to strengthening an approach based on rights and child welfare, it is also necessary to present additional arguments that highlight the importance of investing in comprehensive early childhood development, even in the short term. One such argument is the encouragement for women’s access to the labour market and contribution to the economy when the State can provide quality care and education for their children from birth (Vaca-Trigo, 2019). It is also important to highlight the cost-effectiveness of such investment for productive development and carry out objective studies of the costs associated with inaction.

To deal with a lack of political will, inadequate intersectoral coordination and insufficient allocation of financial resources, there is a need to find partners in all spheres of society who are clear about how strategic, essential and urgent early childhood investment is.

B. Put child-sensitive social protection at the heart of comprehensive early childhood development

Child-sensitive social protection encompasses measures aimed at preventing, reducing and eliminating both the economic and the social vulnerabilities that lead to poverty and social exclusion for children and their families. Considered a fundamental right, social protection contributes directly to children’s development and well-being. By ensuring access to essential services such as nutrition, health, care and education for both children and their families and adequate household incomes, social protection enables children to exercise their rights from an early age, expanding their development opportunities and helping them to reach their full potential (UNICEF, 2012).

Universal, comprehensive and sustainable social protection systems are a fundamental pillar of the Regional Agenda for Inclusive Social Development, which includes a set of policies designed, among other things, to “guarantee universal access to income that permits an adequate level of well-being, as well as universal access to social services” (ECLAC, 2020, p. 19). One of its objectives is to assess the feasibility of gradually and progressively implementing a universal transfer for children.

The discussion on prioritizing cash benefits for children has gained momentum in the region, especially with the COVID-19 pandemic. These benefits could be universal, quasi-universal or of varying coverage, which would help reduce inequalities from childhood onward in access to goods and services and create a shared base of opportunities to acquire human capabilities and thrive (Robles and Santos Garcia, 2023; Bacil and others, 2022).

C. Ensure that families and communities have the resources to provide nurturing care

Encouraging the active participation of families and communities in parenting is fundamental to comprehensive early childhood development. This entails concrete actions to foster collaboration and mutual support between parents, caregivers and educators, with a special focus on children’s socioemotional well-being.

A key measure is to consider the implementation of parental leave and other investments in the care economy. Ensuring parents have access to care services that enable them to care for and nurture their children during the early years of life is critical. This not only strengthens family ties, but also contributes to an emotionally healthy environment for children.

Another key aspect is to further strengthen the links between families and early childhood educators. Fostering open and effective communication between all those involved in the educational process ensures constant and consistent support for their all-round development. Measures to support parenting also need to be strengthened by providing information and resources to those responsible for raising a child in the home. This includes an equitable distribution of responsibilities in the family, with special attention to the excessive burden of care work on women.

D. Comprehensively improve data collection and child information systems

Accurate, up-to-date information is essential for making informed decisions, designing effective policies and reaching vulnerable children and their families. However, challenges remain in the effort to measure progress towards the SDG targets relating to early childhood in all sectors.

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted, for example, the importance of robust monitoring systems to promptly detect and address threats to children’s health. A key aspect is the need to measure epidemiological risks and conduct effective surveillance of the diseases that affect them. Also, given the context of low immunization rates, it is essential to improve the collection of relevant data to identify those who have not been vaccinated and to ensure that they have access to vaccines and information and their concerns and needs are addressed (UNICEF, 2023a).

It is just as critical to implement or strengthen national information systems that allow children’s health status to be monitored in emergencies and crises. This is essential to ensure an effective response and to protect children in vulnerable situations.

In the field of education, the collection and monitoring of indicators related to early childhood educational development are crucial and present major challenges in the region. There are currently many gaps in the data, especially on children at the earliest ages (0 to 3) and on financing. Current reporting on early childhood education tends to group ECCE data with those for other levels of education, which makes it difficult to obtain an accurate picture of the situation and the challenges facing this level of education. The lack of information hampers the formulation of specific policies and programmes aimed at improving the quality of early childhood education. Strengthening data collection is essential to ensure the quality of early childhood education, as access without quality is not enough.

In a context including major challenges, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and persistent inequalities, it is essential to focus efforts on ensuring that all children have the opportunity to reach their full potential from the very beginning of their lives. This commitment is not only a moral imperative but also a crucial investment in a sustainable and prosperous future for our societies.

E. Increase commitment to early childhood education

Strengthening early childhood education has positive short- and long-term impacts on life trajectories and is a fundamental part of inclusive social development in the region. Despite this, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, recognition of the importance of ECCE did not translate into effective measures to ensure educational continuity. This was the level of education where the fewest strategies for reopening and adaptation to the new situation were implemented. Likewise, fewer assessments were carried out, few measures were implemented to reduce learning gaps, and limited remedial and adaptation actions were taken for those who did not have access to distance education (UNESCO/UNICEF, 2022; ECLAC, 2022).

In addition to addressing the immediate impacts of the pandemic, for example by restoring attendance rates and continuing with efforts to achieve universality by methods such as active searching, efforts are needed to strengthen legal frameworks, improve initial and ongoing teacher training and prioritize the quality of education curricula. These efforts would contribute to the skills needed to create safe, stimulating and rewarding environments in which children have opportunities to learn from the very beginning of their lives. There also remains a need to continue investing in early development and education, devoting at least 10% of the education budget to this, as suggested by UNICEF (UNICEF, 2023b; ECLAC, 2022).

Bibliography

Bacil, F. and others (2022), “Las transferencias en efectivo con enfoque universal en la Región de América Latina y el Caribe”, Research Report, No. 65, Brasilia, International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth (IPC-IG)/United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)/United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF).

Black, R. and others (2013), “Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries”, The Lancet, vol. 382, No. 9890.

Black, R. y otros (2013), “Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries”, The Lancet, 382(9890), 427-451.

Castillo, C. and M. L. Marinho (2022), “Los impactos de la pandemia sobre la salud y el bienestar de niños y niñas en América Latina y el Caribe: la urgencia de avanzar hacia sistemas de protección social sensibles a los derechos de la niñez”, Project Documents (LC/TS.2022/25), Santiago, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC).

Center on the Developing Child (2007), “The Science of Early Childhood Development (InBrief)”, Harvard University [online] https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/inbrief-science-of-ecd/.

Chmielewska, B. and others (2021), “Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis”, The Lancet Global Health, vol. 9, No. 6, Elsevier, 1 June.

ECLAC (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean) (2023), Social Panorama of Latin America, forthcoming.

____(2022), Social Panorama of Latin America, 2022 (LC/PUB.2022/15-P), Santiago.

____(2021), Disasters and inequality in a protracted crisis: towards universal, comprehensive, resilient and sustainable social protection systems in Latin America and the Caribbean (LC/CDS.4/3), Santiago.

____(2020), Regional Agenda for Inclusive Social Development (LC/CDS.3/5), Santiago.

____(2013), Montevideo Consensus on Population and Development (LC/L.3697), Santiago.

ECLAC/FAO (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean/Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) (2020), “Food systems and COVID-19 in Latin America and the Caribbean: Food consumption patterns and malnutrition”, Bulletin, No. 10, Santiago, 16 July..

ECLAC/UNICEF (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean/United Nations Children’s Fund) (2021), “The COVID-19 pandemic: the right to education of children and adolescents in Latin America and the Caribbean”, Challenges, No. 24.

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) and others (2023), The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2023. Urbanization, agrifood systems transformation and healthy diets across the rural–urban continuum, Rome.

Heckman, J. (2013), Giving Kids a Fair Chance (A Strategy that Works), Cambridge, MIT Press.

Marinho, M. L., A. Dahuabe and A. Arenas de Mesa (2023), “Salud y desigualdad en América Latina y el Caribe: la centralidad de la salud para el desarrollo social inclusivo y sostenible”, Social Policy series, No. 244 (LC/TS.2023/115) Santiago, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC).

Maza-Arnedo, F. and others (2022), “Maternal mortality linked to COVID-19 in Latin America: results from a multi-country collaborative database of 447 deaths”, The Lancet Regional Health Americas, vol. 12, No. 100269, August [online] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lana.2022.100269.

Narea, M. and others (2021), “Estudio longitudinal mil primeros días, segunda ola primeros resultados: cuidado y bienestar de las familias en pandemia”, Estudios en Justicia Educacional, Santiago, Centro Justicia Educacional.

OEI (Organization of Ibero-American States for Education, Science and Culture) (2023), Haciendo visible lo invisible en primera infancia: avances, logros y desafíos en el cumplimento de la meta 4.2 de los Objetivos del Desarrollo Sostenible, Madrid.

Osendarp, S. and others (2021), “The COVID-19 crisis will exacerbate maternal and child undernutrition and child mortality in low- and middle-income countries”, Nature Food, vol. 2, No. 7, 19 July.

PAHO/UNICEF/World Bank (Pan American Health Organization/United Nations Children’s Fund) (2021), “Nurturing care” [online] https://www.unicef.org/lac/en/parenting-lac/nurturing-care.

Restrepo-Méndez, M. C. and others (2015), “Time trends in socio-economic inequalities in stunting prevalence: analyses of repeated national surveys”, Public Health Nutrition, vol.18, No. 12.

Robles, C. and R. Santos Garcia (2023), “Final recommendations”, Income support and social protection in Latin America and the Caribbean: debates on policy options, R. Santos Garcia, C. Farías and C. Robles (coords.), Project Documents (LC/TS.2023/27/Rev.1), Santiago, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC).

UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) (2022), World Conference on Early Childhood Care and Education: Tashkent Declaration and Commitments to Action for Transforming Early Childhood Care and Education, Paris.

UNESCO/UNICEF (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization/United Nations Children’s Fund) (2022), Education in Latin America and the Caribbean in the second year of COVID-19, Paris.

UNESCO/UNICEF/ECLAC (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization/United Nations Children’s Fund/Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean) (2022), Education in Latin America and the Caribbean at a crossroads: regional monitoring report SDG4 - Education 2030, Paris.

UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund) (2023a), The State of the World’s Children 2023: For every child, immunization, UNICEF Innocenti – Global Office of Research and Foresight, Florence.

____(2023b), Shape the Future of Education in Latin America and the Caribbean: Early Childhood Education for All, Geneva.

____(2021), “Tracking the situation of children during COVID-19», UNICEF DATA. Disponible [online] https://data.unicef.org/resources/rapid-situation-tracking-covid-19-socioeconomic-impacts-data-viz/.

____(2012), Integrated Social Protection Systems: Enhancing Equity for Children. UNICEF Social Protection Strategic Framework, New York.

United Nations (2005), “General Comment No. 7 (2005). Implementing child rights in early childhood” (CRC/C/GC/7/Rev.1), Geneva, 14 November.

____(1989), “Convention on the Rights of the Child” [online] https://www.ohchr.org/es/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-child.

Vaca Trigo, I. (2019), “Oportunidades y desafíos para la autonomía de las mujeres en el futuro escenario del trabajo”, Gender Affairs series, No. 154 (LC/TS.2019/3), Santiago, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC).

WHO (World Health Organization) (2018), Nurturing care for early childhood development: a framework for helping children survive and thrive to transform health and human potential, Geneva.

World Bank/UNDP (United Nations Development Programme) (2021), “COVID-19 Household Monitoring Dashboard” [online] https://www.worldbank.org/en/data/interactive/2020/11/11/covid-19-high-frequency-monitoring-dashboard.

1 These include, in particular, target 2.2 (end all forms of malnutrition), target 3.1 (reduce the global maternal mortality ratio to less than 70 per 100,000 live births), target 3.2 (end preventable deaths of newborns and children under 5), target 3.4 (reduce by one third premature mortality from non-communicable diseases), target 4.2 (access to quality early childhood development, care and pre-primary education), and target 5.3 (eliminate all harmful practices, such as child, early and forced marriage and female genital mutilation).

2 The exceptions are Argentina, Brazil and Costa Rica, with an increasing trend for chronic child undernutrition.

3 Zero-dose children are those who have not received any vaccinations. DTP1 vaccination is used as a proxy for this calculation. Undervaccinated children are those who have received some but not all of the vaccines in the recommended schedule.

4 The official primary school starting age is 6 in most countries of the region.

5 ECLAC and UNICEF conducted a survey with ministries of education, ministries of social development and UNICEF country offices in the Latin America and Caribbean region between December 2022 and February 2023. Responses were received from 26 countries.